The celts

The celts

Celtiberians

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Celtiberians were Celtic-speaking people of the Iberian Peninsula in the final centuries BC. The group originated when Celts migrated from Gaul and integrated with the local pre-Indo-European populations, in particular the Iberians.

Archaeologically, the Celtiberians participated in the Hallstatt culture in what is now north-central Spain. The term Celtiberi appears in accounts by Diodorus Siculus,[1] Appian[2] and Martial[3] who recognized a mixed Celtic and Iberian people; Strabo saw the Celts as the more dominant group in this blend. Extant tribal names include the Arevaci, Belli, Titti, and Lusones.

The Celtiberian language is attested from the first century BC. Other possibly Celtic languages, like Lusitanian, were spoken in pre-Roman Iberia. The Lusitani gave their name to Lusitania, the Roman province name covering current Portugal and Extremadura.

History

Early Celts migrated into the Iberian peninsula and penetrated as far as Cadiz, bringing aspects of Hallstatt culture in the sixth to fifth centuries BC, adopting much of the culture they found.[4] This basal Indo-European culture was of seasonally transhumant cattle-raising pastoralists protected by a warrior elite, similar to those in other areas of Atlantic Europe, centered in the hill-forts, locally termed castros, that controlled small grazing territories. These settlements of circular huts survived until Roman times across the north of Iberia, from Northern Portugal, Asturias and Galicia to the Basque Country.

Celtic presence in Iberia likely dates to as early as the sixth century BC, when the castros evinced a new permanence with stone walls and protective ditches. Archaeologists Martín Almagro Gorbea and Alvarado Lorrio recognize the distinguishing iron tools and extended family social structure of developed Celtiberian culture as evolving from the archaic castro culture which they consider "proto-Celtic".

Archaeological finds identify the culture as continuous with the culture reported by Classical writers from the late 3rd century onwards (Almagro-Gorbea and Lorrio). The ethnic map of Celtiberia was highly localized however, composed of different tribes and nationes from the third century centered upon fortified oppida and representing a wide ranging degree of local assimilation with the autochthonous cultures in a mixed Celtic and Iberian stock.

The cultural stronghold of Celtiberians was the northern area of the central meseta in the upper valleys of the Tagus and Douro east to the Iberus (Ebro) river, in the modern provinces of Soria, Guadalajara, Zaragoza and Teruel. There, when Greek and Roman geographers and historians encountered them, the established Celtiberians were controlled by a military aristocracy that had become a hereditary elite. The dominant tribe were the Arevaci, who dominated their neighbors from powerful strongholds at Okilis (Medinaceli) and who rallied the long Celtiberian resistance to Rome. Other Celtiberians were the Belli and Titti in the Jalón valley, and the Lusones to the east. Excavations at the Celtiberian strongholds Kontebakom-Bel Botorrita, Sekaisa Segeda, Tiermes[5] complement the grave goods found in Celtiberian cemeteries, where aristocratic tombs of the 6th to 5th centuries give way to warrior tombs with a tendency from the 3rd century for weapons to disappear from grave goods, either indicating an increased urgency for their distribution among living fighters or, as Almagro-Gorbea and Lorrio think, the increased urbanization of Celtiberian society. Many late Celtiberian oppida are still occupied by modern towns, inhibiting archeology.

Metalwork stands out in Celtiberian archeological finds, partly from its indestructible nature, emphasizing Celtiberian articles of warlike uses, horse trappings and prestige weapons. The two-edged sword adopted by the Romans was previously in use among the Celtiberians, and Latin lancea, a thrown spear, was a Hispanic word, according to Varro. Celtiberian culture was increasingly influenced by Rome in the two final centuries BC.

From the third century, the clan was superseded as the basic Celtiberian political unit by the oppidum, a fortified organized city with a defined territory that included the castros as subsidiary settlements. These civitates as the Roman historians called them, could make and break alliances, as surviving inscribed hospitality pacts attest, and minted coinage. The old clan structures lasted in the formation of the Celtiberian armies, organized along clan-structure lines, with consequent losses of strategic and tactical control.

The Celtiberians were the most influential ethnic group in pre-Roman Iberia, but they had their largest impact on history during the Second Punic War, during which they became the (perhaps unwilling) allies of Carthage in its conflict with Rome, and crossed the Alps in the mixed forces under Hannibal's command. As a result of the defeat of Carthage, the Celtiberians first submitted to Rome in 195 BC; T. Sempronius Gracchus spent the years 182 to 179 pacifying (as the Romans put it) the Celtiberians; however, conflicts between various semi-independent bands of Celtiberians continued. After the city of Numantia was finally taken and destroyed by Scipio Aemilianus Africanus the younger after a long and brutal siege that ended the Celtic resistance (154 - 133 BC), Roman cultural influences increased; this is the period of the earliest Botorrita inscribed plaque; later plaques, significantly, are inscribed in Latin. The war with Sertorius, 79 - 72 BC, marked the last formal resistance of the Celtiberian cities to Roman domination, which submerged the Celtiberian culture.

The Celtiberian presence remains on the map of Spain in hundreds of Celtic place-names. The archaeological recovery of Celtiberian culture commenced with the excavations of Numantia, published between 1914 and 1931.

The celts

20th September 2006

Ola! Spanish have Celtic Britons descendants

Scientists have discovered the British are descended from a tribe of Spanish fishermen. DNA analysis has found the Celts — Britain's indigenous population — have an almost identical genetic "fingerprint" to a tribe of Iberians from the coastal regions of Spain who crossed the Bay of Biscay almost 6,000 years ago.

People of Celtic ancestry were thought to have descended from tribes of central Europe. But Bryan Sykes, professor of human genetics at Oxford University, said: "About 6,000 years ago Iberians developed ocean-going boats that enabled them to push up the Channel.

"Before they arrived, there were some human inhabitants of Britain, but only a few thousand. These people were later subsumed into a larger Celtic tribe... the majority of people in the British Isles are actually descended from the Spanish."

A team led by Professor Sykes — who is soon to publish the first DNA map of the British Isles — spent five years taking DNA samples from 10,000 volunteers in Britain and Ireland, in an effort to produce a map of our genetic roots.

The most common genetic fingerprint belongs to the Celtic clan, which Professor Sykes has called "Oisin". After that, the next most widespread originally belonged to tribes of Danish and Norse Vikings. Small numbers of today's Britons are also descended from north African, Middle Eastern and Roman clans.

These DNA fingerprints have enabled Professor Sykes to create the first genetic maps of the British Isles, which are analysed in his book Blood Of The Isles, published this week. The maps show that Celts are most dominant in Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

But the Celtic clan is also strongly represented elsewhere in the British Isles. "Although Celts have previously thought of themselves as being genetically different from the English, this is emphatically not the case," said Professor.

Celtic language

Orígenes

Las lenguas celtas derivan de un conjunto de dialectos del proto-indoeuropeo, idioma que cronológicamente ocupa una posición intermedia dentro de la familia indoeuropea, pues hizo su aparición después de las lenguas anatolias (2000 a. C.), el griego (1400 a. C.), las lenguas índicas (1000 a. C.), las lenguas iranias (700 a. C.) y las lenguas itálicas (600 a. C.), pero antes de las lenguas germanas (siglo I d. C.), las lenguas eslavas (siglo IV), el armenio (siglo V), el tocario (siglo VII), las lenguas bálticas (siglo XV) y el idioma albanés (siglo XVI).

Sus hablantes eran los pueblos celtas, una serie de tribus y clanes de la Europa Central y Occidental que compartían unas características culturales similares: creencias religiosas, estructura social, estilos artísticos, sistemas de producción, y sobre todo una lengua común, o más bien una serie de dialectos inteligibles entre sí. El nombre que utilizaban para designarse a sí mismos era *gal- o *kel-, como reflejan los nombres de sus lenguas y los nombres de los pueblos celtas:

- Galli (pueblos galos de la Gallia, región que comprende básicamente Francia y Bélgica),

- Gálatae o Gálatai (gálatas, celtas de una provincia romana en el centro de la actual Turquía llamada Galatia),

- Galaici (celtas de Galicia, al noroeste de Hispania)

- Gaelige (celtas de Irlanda)

- Keltoi (nombre general usado por los griegos)

El nombre celta procede del griego keltoi, término que usaban los geógrafos griegos en la primera mitad del I milenio a. C. para designar a los pueblos que habitaban Europa central.

Aunque se encuentran esparcidas diversas alusiones a los celtas en Hecateo de Mileto, Heródoto y Aristóteles, la primera referencia a este pueblo se halla en la Ora Maritima de Avieno, procónsul en África en el 336 d.C., quien se basó en un original griego del siglo VI a.C. Los romanos los llamaban galli (pronunciado gal-li).

Existen varias hipótesis respecto a la aparición de las lenguas celtas, de las cuales varias son mutuamente excluyentes. Estas hipótesis han afectado a la clasificación filogenética de las lenguas celtas: algunos autores clasifican las lenguas célticas insulares como una unidad frente a las lenguas célticas continentales. Otra clasificación propugna la existencia de una relación galo-britónica de un origen más arcaico, frente al goidélico, el idioma celtíbero y el idioma lepóntico.

Prehistoria de los pueblos celtas

El término celta (keltoi) es de origen griego; éstos pudieron haberlo tomado prestado de íberos o ligures. Los celtas probablemente se llamaban a sí mismos *gal-,[cita requerida] o sea: galos (derivados: gálata, gallego, galaico).

No parece posible discernir etnias propiamente celtas entre los primeros grupos de indoeuropeos que penetraron en la Europa central. Sólo hasta el siglo V a. C., con el surgimiento de la cultura de La Tène es razonablemente seguro identificar a los portadores de esa cultura como hablantes de lenguas celtas. Los primeros pobladores indoeuropeos podrían haber sido los portadores de la Cultura de los campos de urnas, que se expandieron rápida y extensamente por Europa hacia el siglo XIII a. C. Los miembros de esta cultura se expandieron descendiendo por la margen derecha del Ródano, ocupando Languedoc, Cataluña y el bajo valle del Ebro. Otra línea de expansión les llevó a Bélgica y el sureste británico. A partir del siglo VIII a. C., otros pueblos presuntamente indoeuropeos (tal vez pre-celtas y pre-ilirios) fueron los portadores de la cultura de Hallstatt (Hierro-I), extendiéndose en esta fase por el interior de la Península Ibérica (s. VII). En el siglo VI a. C., los pueblos presuntamente indoeuropeos fueron desplazados del noreste ibérico a manos de los íberos, quedando así los celtas de Iberia aislados del resto de pueblos celtas continentales.

Desde el siglo IV a. C., los celtas continentales inauguran la cultura de La Tène, específicamente celta (Hierro II). En esta fase, los celtas acabaron de ocupar el norte y centro de Francia (la Galia), así como la mayor parte de las islas británicas. También se extendieron por los Balcanes, alcanzando incluso una comarca de Asia Menor, que será conocida como Galatia. En esta época se construyen importantes villas fortificadas (lat. oppida), que funcionan como centros comerciales y políticos. Es también en este período cuando el druidismo, descendiente de los antiguos cultos megalíticos de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda[cita requerida], se introduce entre los celtas de las islas, pasando posteriormente al continente.

Historia y referencias clásicas

A partir de los siglos II y III a. C. algunos autores clásicos ofrecen datos concretos sobre la historia de los pueblos celtas. Los romanos usaron el término galli para referirse a varios pueblos celtas, entre los cuales estarían los galos, los gálatas, o regiones como la Galia, Gallaecia o Galizia. Sin embargo, aunque los romanos se refirieran a las tribus por sus nombres individuales (aedui, belgae, helvetti, boii...), sí reconocen ciertas características culturales comunes entre éstas. La unidad lingüística de estos pueblos es puesta de manifiesto por Tácito al percibir la similitud entre las lenguas britónicas y las galas. San Jerónimo dejó constancia en sus escritos de que la lengua de los gálatas le resultaba parecida al dialecto galo de Tréveris.

Los pueblos celtas se expandieron entre los siglos VIII y V a. C. desde su núcleo original centroeuropeo hacia otras regiones, ocupando el norte y centro de Francia (la Galia), el valle del Po en el norte de Italia, la península Ibérica, así como la mayor parte de las islas británicas. También se extendieron por los Balcanes, alcanzando incluso una comarca de Asia Menor, que será conocida como Galatia.

En todas estas migraciones su lengua les acompañó allá donde fueran; en el siglo I a. C. se extendían por gran parte de Europa, desde la actual Turquía (Galacia) hasta Portugal. Sin embargo, las lenguas célticas encontraron refugio a la romanización en el extremo noroccidental de Europa, en las islas Británicas. A partir del siglo II a. C., los celtas acusan la creciente presión militar de los germanos por el norte y, algo después, la de los romanos por el sur. En pocas décadas «toda la Galia está ocupada», excepto Irlanda. De todas formas, la presencia romana en Gran Bretaña fue también de escasa duración, lo que permitió a las lenguas celtas de esta isla (galés) sobrevivir y, más tarde, regresar al continente (Bretaña francesa). Todavía en el siglo VII, los celtas llevaron a cabo su quizá última expansión: los escotos irlandeses invadieron Caledonia y le cambiaron el nombre por el de Escocia.

Declive

Si bien en la Antigüedad fueron habladas ampliamente en Europa occidental en el primer milenio a. C., las lenguas celtas han experimentado un declive gradual desde los tiempos romanos, bien reemplazadas primero por el latín y luego por las lenguas romances en Francia, Portugal, Italia y España, bien desplazadas y sustituidas por otras ramas como la germana en las islas Británicas y Europa Central o la eslava en los Balcanes, o bien por la disipación e integración del pueblo celta y de sus lenguas dentro de nuevas realidades históricas. A pesar de estos hechos, hubo pequeñas islas lingüísticas que sobrevivieron bastante tiempo a este influjo, hallándose testimonios de gálatas hablantes de lengua celta en el siglo IV d. C.

Las lenguas celtas mantuvieron mayor vigor en las islas británicas. Allí las lenguas nativas gaélicas y britónicas mantuvieron su hegemonía hasta la Edad Media, siendo la lengua predominante en el Reino de Escocia y en los condados y reinos irlandeses y galeses. Su declive en Gran Bretaña comenzó con las invasiones anglosajonas, quedando reducida su presencia tras la Muralla de Offa a Gales y al Reino de Escocia. Unos siglos más tarde, también empezaron a perder peso y presencia las lenguas célticas en estas regiones y en Irlanda debido principalmente la pérdida de independencia política y cultural, así como por el aislamiento económico, en detrimento del entonces pujante Reino de Inglaterra en el siglo XVI, si bien este proceso se dio de manera lenta y constante desde siglos atrás. La lengua hablada en la isla de Man se vería muy influenciada por aportes nórdicos, fruto de las sucesivas invasiones vikingas.

El origen del bretón, si bien se podría pensar fácilmente debido a su situación geográfica que es un reducto de la lengua gala hablada en época prerromana en la actual Francia, se remonta a migraciones de británicos (principalmente de las zonas de Cornualles y Gales) en el siglo V d. C. que huían de las invasiones anglosajonas a Gran Bretaña, estableciéndose tras cruzar el canal de la Mancha en la costa de Armórica, la actual Bretaña. Algunos de estos britanos llegaron incluso a la Península Ibérica, concretamente al norte de la Gallaecia, region histórica que incluía la Galicia actual y buena parte de Asturias y el norte de Portugal, donde fundaron el obispado de Britonia, al frente del cual estaría el celebre obispo Mailoc, mencionado en los concilios galaicos de Lugo y de Braga en el siglo VI de nuestra era.

Pese a su lento declive con los siglos, hoy día aún sobrevivien, únicamente, cuatro lenguas de la rama céltica, limitadas a pequeñas regiones de Europa: el idioma irlandés o gaélico irlandés en Irlanda, el gaélico escocés o escocés (nombre que lleva a la confusión con el también llamado escocés, idioma germánico) en Escocia, el idioma galés en Gales y el idioma bretón en Bretaña. Asimismo, hasta el siglo XVIII en Cornualles se hablaba el idioma córnico, de gran semejanza con el bretón y el galés. Hasta principios del siglo XX en la isla de Man se hablaba el idioma manés. También, fruto de la emigración, hay pequeñas colonias de hablantes de lengua celta en la Patagonia argentina y en algunas partes de Canadá.

Sin embargo, en mayor o en menor medida pero en la mayoría de los casos muy reducido, generalmente las lenguas posteriormente habladas en regiones de lengua celta mantienen un sustrato céltico en su vocabulario, como pueden ser el español, el francés, el portugués, el inglés o el alemán.

Literatura

Los textos de las lenguas célticas continentales son muy escasos y la mayoría son pequeñas inscripciones, monedas, glosas y nombres. Las inscripciones en galo van del siglo III a. C. al siglo I d. C., destacando el Calendario de Coligny (del siglo II d. C.), y suelen estar escritas en letras latinas. En lepóntico han sido encontradas, escritas en una variante del alfabeto etrusco y de fechas anteriores al siglo I, en el norte de Italia. Los textos en celtibérico son pequeñas inscripciones en piedra o en bronce cuya datación abarca desde el siglo III a. C. hasta el siglo I d. C.; se destaca el Bronce de Botorrita.

Sin embargo, las lenguas célticas insulares sí disponen de una extensa y variada literatura, siendo de las más antiguas de Europa. Escrita originalmente en monumentos pétreos en escritura ogham en Gales y, principalmente, en Irlanda desde el siglo IV hasta el VI d. C., posteriormente se redactaron manuscritos en irlandés durante la Edad Media, como el Ciclo de Ulster o los Anales de los cuatro maestros.

Ya en el siglo XX, se destacan dos escritores en irlandés, Michael Hartnett y el premio Nobel Seamus Heaney. También existe desde la Edad Media literatura en bretón, escocés y en galés, en algunos casos manteniéndose viva hasta hoy en día.

Clasificación de las lenguas celtas

Las lenguas celtas pertenecen la rama occidental de la familia indoeuropea, y dentro de ésta al grupo de las lenguas centum. El estudio de las lenguas celtas antiguas se ha basado ocasionalmente en conjeturas debido a la falta de fuentes primarias. La clasificación interna de las lenguas célticas se puede hacer desde dos puntos de vista: geográfico y lingüístico.

Clasificación geográfica

La subdivisón geográfica de estas lenguas nos lleva a clasificarlas en dos grupos:

- Lenguas célticas insulares

- Lenguas goidélicas

- el gaélico escocés, en Escocia.

- el irlandés o gaélico irlandés, en Irlanda, siendo lengua oficial de la República de Irlanda.

- el manés, en la isla de Man.

- Lenguas britónicas

- el galés, nacido de un dialecto occidental y septentrional, hablado hoy en día en Gales.

- el cúmbrico, nacido de un dialecto septentrional, hablado hasta el siglo XII en el noroeste de Inglaterra y el sur de Escocia.

- el córnico o cornuallés, nacido de un dialecto sudoccidental, hablado en Devon, Cornualles y partes de Somerset y Dorset hasta el siglo XVIII.

- el bretón, de gran similitud con el córnico y el galés, llevado a Bretaña por emigrantes de esas regiones.

- el picto, si bien su filiación céltica no está clara aún.

- Lenguas goidélicas

Respecto al ivérnico o paleoirlandés no se tiene clara su filiación britónica o goidélica.

- Lenguas célticas continentales

- el galo, en la antigua Galia (actuales Francia y Bélgica).

- el celtíbero, celtibérico o hispano-celta, en la antigua Celtiberia (en la actual España).

- el lepóntico, en la antigua Galia Cisalpina (en la actualidad, considerado muchas veces como un dialecto del galo)

- el gálata, de gran similitud con el galo según San Jerónimo, en Galatia en Anatolia (actual Turquía).

- el nórico, hablado por la tribu nórica en tierras de las actuales Austria y Baviera e igualmente cercano al galo.

- En caso de confirmarse la filiación céltica del lusitano, asunto aún en discusión, éste también quedaría englobado en este subgrupo.

Clasificación lingüística

La división de las lenguas célticas por un criterio lingüístico las separa en dos grupos1 : lenguas célticas P, o Grupo-P, y lenguas célticas Q, o Grupo-Q. La diferencia entre unas y otras radica en cómo evolucionó el sonido *kw, que se transformó en *p en algunos y en *k en otros.

Diversos estudios afirman que las lenguas celtas Q derivarían de las primeras oleadas culturales de la cultura de Hallstatt celta de entre los siglos VIII y VI a. C., que se extendieron por el centro y noroeste de Europa hasta la península Ibérica. El supuesto idioma común de estos pueblos, que luego se bifurcaría, conservaba muchos de los rasgos del indoeuropeo original, entre ellos la ya mencionada conservación del sonido *kw. Incluso, se habla de un subgrupo italo-céltico para referirse a estas lenguas, por su supuesta similitud con las lenguas itálicas.

Asimismo, las lenguas celtas P provendrían de una segunda oleada cultural celta igualmente proveniente de centroeuropa, pero con unos patrones culturales diferentes marcados por la Cultura de La Tène, y que ocuparon Europa central y occidental desde la isla de Gran Bretaña, a través del norte de Italia, hasta del valle del Danubio y el norte de Anatolia (Turquía). El principal rasgo de estas lenguas, como se dijo ya, consiste en la sustitución del sonido *kw por el sonido *p.

Esta teoría se apoya, además de las teorías lingüísticas, en el hecho geográfico de que los pueblos que conservaron las lenguas celtas-Q se encuentran en los extremos occidentales de Europa, Irlanda, Escocia y la península Ibérica, como si éstos hubiesen sido desplazados hacia el oeste por otras migraciones, mientras que las celtas-P ocupan el centro de Europa y del área de la cultura celta.

Céltico P

En las lenguas pertenecientes a este primer grupo el sonido labiovelar indoeuropeo /*kw/ se reduce a /p/. A este grupo pertenecerían las lenguas británicas, el lepóntico, el gálata y la mayor parte del galo.

Céltico Q

En cambio, en las lenguas de este segundo grupo, el sonido /*kw/ indoeuropeo se mantuvo durante la época antigua, deslabializándose en /k/ más tardíamente. Dentro de este grupo quedarían englobadas las lenguas goidélicas (irlandés, gaélico escocés y manés) y el celtíbero.

Comparativa léxica del celta-P y el celta-Q

| Proto-Celta | Galo | Galés | Bretón | Irlandés | Gaélico Escocés | Manés | Español |

| *kwennos | pennos | pen | penn | ceann | ceann | kione | cabeza |

| *kwer- | pryf | cruim | caliente | ||||

| *kwrei- | prynu | crenaim | compra | ||||

| *kwrmi- | pryd | cruth | forma | ||||

| *kwetwar- | petuarios | pedwar | pevar | ceathair | ceithir | kiare | cuatro |

| *kwenkwe | pinpetos | pump | pemp | cúig | còig | queig | cinco |

| *kweis | pis | pwy | piv | cé [< cia] | cò/cia | quoi | quién |

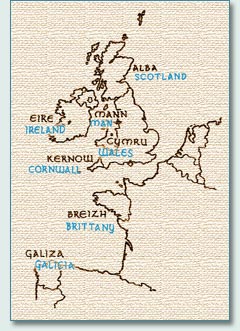

Celtic Galicia

Galicia is a Celtic region of north-west Spain, with its own regional parliament, the Galician Council, or 'Xunta de Galicia". It is bordered on the east by the other Celtic region of Asturias, and to the south by the country of Portugal.

This Atlantic corner of North-west Spain, known as "the land of the 1000 rivers", has a mountainous inland area, and a rugged coastline of cliffs, lagoons, beautiful beaches and small islands. The landscape is dotted with ancient dolmen, hill forts, and stone crosses and chapels.

The native name for the land is Galiza, and the people are Galegos. An ancient Celtic mother goddess named Cailleach, who's name in Latin was 'Calaicia', is probably where the name Galicia originated, with the Romans calling the land Gallaecia, and the people the Gallaeci.

The Galician language is one of the four official languages of Spain, spoken by most of the inhabitants of the region. The folklore of the area shows its Celtic origins, and the traditional musical instrument is the 'Gaita', or bagpipe.

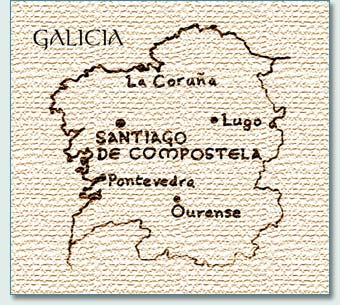

The Region's capital city is Santiago de Compostela, and it's four provinces are A Coruna, Lugo, Ourense and Pontevedra, with a population of almost 3 million.

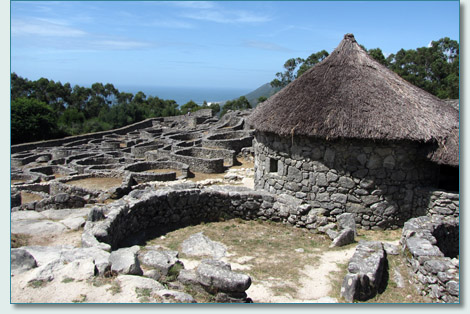

The ancient people of Galiza left a stone legacy of thousands of Dolmen (three standing stones with a huge slab across the top, forming burial chambers), or 'Mamoas'. The Celtic tribes had heavily settled the area by the 5th century B.C., and lived in 'Castroes', circular fortified settlements of several buildings surrounded by a defensive ditch, normally situated on hilltops.

Celtic ruins of Castro de Santa Tegra, southern Galicia, looking south

South of the capital of Vigo - a big city with an old medieval town center - are the out-of-the-way Celtic ruins of Castro de Santa Tegra (Santa Tecla), high on Mount Santa Tegra, overlooking the surf of the Atlantic Ocean. An ancient Celtic settlement of hundreds of round stone-walled dwellings, dating from at least the 2nd to 1st centuries BC, the ruins have spectacular views - south over the Rio Miño, and across to what is now Portugal, and to the north along the Galician coast and the town of A Guarda.

Celtic ruins of Castro de Santa Tegra, southern Galicia, looking north

Re-discovered in 1913, with the last excavation in 1988, only part of the ruins have been uncovered, showing houses, stores, workshops, yards and granaries, and even rainwater ditches and tanks. The population may have been 3000-5000 people of the Grovii tribe, and it is thought this was an important center controlling maritme traffic along the coast and up-river, dying off after the arrival of the Romans, with their new roads and settlements on lower land.

Also up the mountain is an old Christian pilgrimage road, lined with huge crosses and rest areas, with many stairs leading to the old hermitage of Santa Tegra, with it's courtyard and outbuildings. At the summit there is a good museum, cafe, and many stalls selling local Galician souvenirs !

Hermitage of Santa Tegra

Legend has it that the ancient Galicians sailed from the north-west coast of their land, to settle in Ireland. According to the archaic text Lebor Gabala Erenn, the Book of Invasions of Ireland, the descendants of Gaedheal Glas, the father of all Gaels, settled here, one of the Chiefs being Breoghan, son of Brath. Breoghan founded Brigantia (La Coruna), and built a tower by the ocean. The tale goes that on a clear evening, one of his ten sons, Ithe, saw a far-off island, told his brothers, and set sail the next day with his own son Lugaid and more, only to be killed by local noblemen of the island. Ithe's brother Bile retuned with a force to Ireland to avenge his death, and settled after their victory. Bile's son called Mil gave his name to the Milesians, conquerors of Ireland and fathers of the Gaelic race. Mile, the founder of that race, was married to Scota ( who may have given her name to the later Irish settlers of Scotland), and their son, Breoghan, became Galicia's ancient hero.

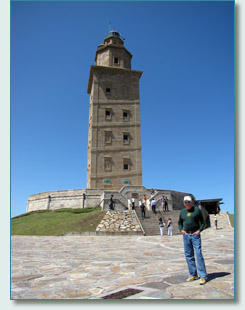

Breoghan is said to have built the oldest lighthouse in the Atlantic world at Brigantia - the end of the known Celtic world to the ancients in Europe, Finisterra, or Land's End - later rebuilt by the Romans, and today called A Coruna or La Coruna.

L - Gaelic chief Breoghan who's sons sailed to Ireland from Brigantia (La Coruna)

R - Chuck Wall by the oldest working lighthouse in Europe at La Coruna

The popular coastal resort and surf spot is home to the oldest continuously working lighthouse in Europe. Originally built by the Romans, who occupied Brigantia, you can still see the ancient foundations they built under the 17th century existing lighthouse. The view of the surrounding coastline from the top is spectacular, not to mention the huge tiled compass rose with images representing the Celtic nations, plus one local legend. The nations are named in their own native languages.

Celtic Nations compass rose, La Coruna, Galicia, Spain

The Romans occupied Galicia for its rich mining, and left town walls and bridges that remain to this day.

The Swabians ruled the land for 170 years, calling it Suevia, until overrun by Visigoths, who in 711 A.D. had their larger Spanish kingdom invaded and taken by Islamic warriors, who left Galiza largely untouched.

Long after the arrival of the Christian Church, the discovery, in the Middle Ages, of the tomb of the Apostle Santiago (St.James), started the pilgrimages of thousands to the cathedral of the new town of Santiago de Compostela, and resulted in the famous 'Way of Santiago', or 'Way of St.James', with its numerous monasteries, churches, and chapels.

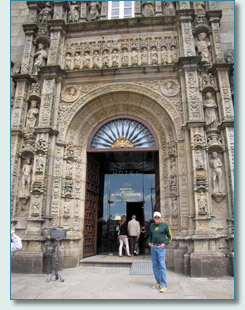

Hostal de los Reyes Católicos (left) - (right) Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela

The city is home to the Hostal de los Reyes Católicos, a fabulous 15th century building, originally a hospital, across the Praza do Obradoiro from the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela.

The Camiño de Santiago has been a pilrimage route since the 10th century, with Christian travellers heading from all over Europe to pay homage to St.James the Apostle, who brought the new religion to the Celts of the Iberian Peninsula. His relics were rediscovered here in 814, the first church being buit in 829, and the existing cathedral started in 1075 and finished in 1122.

The Camiño de Santiago has been a pilrimage route since the 10th century, with Christian travellers heading from all over Europe to pay homage to St.James the Apostle, who brought the new religion to the Celts of the Iberian Peninsula. His relics were rediscovered here in 814, the first church being buit in 829, and the existing cathedral started in 1075 and finished in 1122.

The old pilgrimage road is now one for hikers and cyclists, who happily arrive in the main square, the Praza do Obradoiro, at the end of their long journey. There can often be heard the sound of the Galician bagpipe, the gaita galega, played by gaiteros in traditional costume.

Right - Galician piper gaitero Pedro Perez

The country was ruled by the King of Galiza and Leon, a neighbouring region, until Ferdinand 3rd, King of Castille absorbed it into his expanding kingdom.

Several hundred years later the Galician culture and language was only alive in the poorer people of the land, until a 19th century revival, which intensified into the next century. Various Nationalist parties arose in the 1920s-30s, and the Spanish parliament approved the Autonomy Statute for Galicia in 1937, but it did not come into force because of the Spanish Civil War, and Galicia finally became an Autonomous Community in 1981.

The Celtic music tradition is alive and well in Galicia - our own Hamish recorded a great interview with famous local musician Carlos Nuñez for his radio show, talking about Carlos' career, Celtic history, Galicia and her music, the gaita (bagpipes).

Hamish & Carlos Nuñez, amazing Galicican bagpiper and flute player

his new themed album Alborada Do Brasil, with a Brazilian/Galician musical journey discovered by Carlos while personally researching his great-grandfather, a piper who had emigrated to Brazil, leaving behind a legacy of bagpiping. Carlos' enthusiasm - for Galicia, music, all things Celtic, and life itself - is fabulous, and infectious !

The modern Galician civil flag dates from the 19th century, and is a white field with a diagonal blue band. Originally it was a copy of the naval flag of the Galician port of A Coruña - a blue diagonal St.Andrew's cross over a white field, as the saint is popular in Galicia. It was modified in 1891 due to confusion with the flag of the Imperial Russian Navy, and one of the arms of the cross was dropped.

The modern Galician civil flag dates from the 19th century, and is a white field with a diagonal blue band. Originally it was a copy of the naval flag of the Galician port of A Coruña - a blue diagonal St.Andrew's cross over a white field, as the saint is popular in Galicia. It was modified in 1891 due to confusion with the flag of the Imperial Russian Navy, and one of the arms of the cross was dropped.

The State flag of Galicia dates from the Franco era, with the background of the civil flag, and a coat of arms in the centre. The arms consist of a blue shield topped by a crown, with a yellow goblet surrounded by seven white crosses. This comes from the old flag of the Kingdom of Galicia before the creation of the modern flag in the 19th century, with the goblet being the Holy Grail, by legend kept at Finisterre, Galicia, before being removed to the British Isles. The Apostle St.James relics are buried in the fabulous 10th century Cathedral in Santiago de Compostello, one of seven Galician cities represented by the crosses on the shield, and is said to have brought the Chalice from the Last Supper to 'the land's end' of Galicia.

The State flag of Galicia dates from the Franco era, with the background of the civil flag, and a coat of arms in the centre. The arms consist of a blue shield topped by a crown, with a yellow goblet surrounded by seven white crosses. This comes from the old flag of the Kingdom of Galicia before the creation of the modern flag in the 19th century, with the goblet being the Holy Grail, by legend kept at Finisterre, Galicia, before being removed to the British Isles. The Apostle St.James relics are buried in the fabulous 10th century Cathedral in Santiago de Compostello, one of seven Galician cities represented by the crosses on the shield, and is said to have brought the Chalice from the Last Supper to 'the land's end' of Galicia.

The Celts

The Celts as a Proto-Historic People

The name 'Celt' has been messed about with over the years to the point that the true meaning has all but disappeared.

In the first instance the Greeks and the Romans knew of a tribe called Keltoi. From that point, all the people that looked or behaved the same were called 'Keltoi', regardless of the true name of the individual tribal group.

Over the centuries the name changed with the languages until it was shortened to Kelt ( with a hard 'K'). This name persisted into the 20th century with books in the 1920's-30's calling the people Kelts and the word celt (pronounced selt) being the name for axe-heads of various kinds.

With the upsurge in interest of our origins the words merged and now we call the people Celts (pronuonced Kelt).

The racial group that we now call Celt were in fact an Indo-European people whose culture spread rapidly across the whole of Europe, up into Scandinavia, down into the Spanish peninsula; and modern thought points to a spread over the Asian sub-continent as far as the borders of China.

This does not mean the people expanded and took over, but that their culture was strong enough to dominate and be adopted by other peoples in the area.

But for the purpose of simplicity the name Celt is used in the following information.

This is a resume of the involvment of the Celtic peoples in Europe and the Romans in Britain. Note:-The use of the name 'CELT' is to make understanding easier, and refers to the Indo-Europian Peoples. | |||

| 1200BC | Start of the Bronze Age Urnfield Culture in central Europe. | ||

| 1000-750BC | Proto-Celtic people of the Urnfield culture dominate much of Continental Europe. Also start to spread out over northern Asia as far as the frontiers of China. Development of the deliberate smelting of iron in the Middle East and China around the same time. Prompting the title 'The Iron Age' for this period. | ||

| 700-500 | Hallstatt culture developes in Austria. | ||

| 700BC | Early Celts in Austria bury iron swords with thier dead. | ||

| 600BC | Greeks found the colony of Massilia, opening up trade between the Celts of inland Europe and the Mediterranean. First evidence of Britain having a name - Albion - (albino, white - called after the chalk-cliffs of Dover). A major rebuild of old Bronze Age defences, and construction of new hillforts takes place in Britain. | ||

| 550-500 | A princess in Vix (Burgundy) is buried with a 280 gallon bronze Greek vase, the largest ever made. 60 miles away a prince is buried layed out on bronze chais-lounge in a hugh chamber tomb. | ||

| 500 | Trade between the Etruscans and the Celts begins. Lá Téne phase of Celtic culture speads through Europe and into mainland Britain. The Greeks record the name of a major tribe - The KELTOI - and this becomes the common name for all of the tribes. | ||

| 500 | Celts (the Gaels - from Galicia) arrive in Ireland from Spain. | ||

| 400-100BC | La Tene culture spreads over Europe and into the British Isles. | ||

| 400 | Celts invade Italy and Cisalpine Gaul. | ||

| 400 | Celts atack the Etruscan city of Clusium. | ||

| 390 | Raiding Celtic tribes under the leadership of Brennus ravage Rome and occupy the city for three months. Offended by the dirty conditions of the city (they were country boys at heart) they demand a ransome to leave the Romans alone. Brennus demands his weight in gold and when the Romans complain he throws his sword on the scales to be weighed as well with the cry "VAE VICTUS" - (Woe to the Vanquished). | ||

| 335 | Alexander recieves envoys from the Celts, and exchange pledges of alliance. Large numbers of Celtic Warriors join the Greeks in a war against the Etruscans. | ||

| 323 | Alexander dies and the Celts push into Macedonia. | ||

| 279 | Celtic tribes invade Greece. | ||

| 275 | Celts establish the state of Galatia (Gauls across the alps) in northern Turkey. | ||

| 250 | |||

| 230 | Galatian Celts defeated in battle by Greek forces in Western Turkey. | ||

| 225 | Roman army routs invading Celtic Gauls at Telamon in central Italy. | ||

| 200 | The Celts establish permanent fortified settlements (Oppida, or towns). | ||

| 191 | Cisalpine Gaul is taken by the Romans. | ||

| 150 | |||

| 121 | Rome takes Provence. | ||

| 100 | Belgae tribes migrate to Britain to escape Roman domination. | ||

| 70 | Druids (a fire cult from the Middle East) arrive in Britain and gain control of the ruling classes. | ||

| 58 | Julius Caesar is made governor of Provence | ||

| 58-51 | Caesar's Gallic Wars | ||

| 58 | Helvettii in Switzerland are attacked by Germanic tribes led by Ariovistus and move to Gaul. Caesar follows them and defeats them at Toulon-sur-Arroux. Dumnorix of the Aedui tries to lead resistance against the Romans and fails. | ||

| 57 | Caesar then turned his attention to the tribes of the Belgae and lays seige to their territory. By autumn, Caesar claims that all the Gallic tribes are subjects of Rome. | ||

| 56 | The Veneti of Brittany seize two Roman envoys, and make a stand. After a long sea battle, Caesar executed the leaders and sold the men of the tribe into slavery. | ||

| 55 | Julius Caesar tries to land in Britain and is pinned down on a beachhead for two months. His cavalry was seasick and was sent back to Gaul. With the aproaching Autumn gales he withdraws from Britain. | ||

| 54 | Caesar prepares another expedition to Britain and attempts to take Dumnorix as a hostage. Dumnorix refuses and the Romans kill him. As he dies he cries "I am a freeman in a free state". Inspired by his actions, Ambiorix of the Eburones leads an attack against the Roman garrison and massacres them. Ambiorix recruits the Belgic tribes, the Nervii and Aduatuci, and lay seige to the garrison at Namur. The attack is so successful that Caesar himself had to lead the relieving army to drive them off. | ||

| 53 | The tribes of Gaul unite under the leadership of Indutiomarus of the Treveri. The Celtic army consisted of the Treveri, Senones, Carnutes, Nervii, Aduatuci and Eburones. Indutiomarus attacks Caesar's headquarters at Mouzon and lays seige. After a great fight, the Romans kill Indutiomarus. There then followed a number of uprisings among the tribes and Caesar has to work his way through the tribes putting down revolts. Acco of the Senones and the Carnutes was flogged and then put to death. Ambiorix was trailed by a Roman troop until he disappeared into the Ardennes forest, and was never heard from again. | ||

| 52 | A war leader called Vercingetorix ( « Read more about him) emerges to take control of the Celtic army. He maintains a running battle from three successive hill forts. The last one was called Aelisia and Ceasar laid siege for three months with no effect and had to defend himself from from constant attack by the Celtic warriors. Vercingetorix finely surrenders. | ||

| 45 | Caesar ordered that Vercingetorix was to be taken to Rome. He was paraded through the streets then executed as a dangerous enemy of Rome. | ||

0 | Birth of Christ. (Acording to the church of Rome under Constantine) | ||

| AD38 | Caligula parades Celtic captives through Rome. | ||

| AD39 | The Catevaulauni under the Kingship of Cunobelinus and his sons Caratacus and Togidubnus, expand into the Atrebate (Hampshire) and the Trinovante (Suffolk). | ||

| AD41 | Petition put in to Rome for assistance, turned down because of the civil wars in Rome. | ||

| AD43 | Verica of the Atrebates petitions Claudius to come to Britain to help against the Catevaulauni. | ||

| AD 43 | Claudian invasion with four legions under Aulus Plautius. Defeat of Caratacus and capture of Camulodunum. Expansion into the midlands (XX Valeria Victrix and XIV Gemina) and in the east (IX Hispana). Frontier established west of Fosse Way. Caractacus escapes into the Welsh borders and fights the Romans using guerilla tactics. Once it is safe to do so, Claudius comes to Britain in person to claim it for Rome. He rides an elephant into the new town of Londinium, stays for two weeks, then goes back home. | ||

47 | New governor, Ostorius Scapula, governor, draws a frontier from the Trent to the Severn. Campaigns in the west (Legio II Augusta under Vespasian) | ||

49 | Colonia of Camulodonum (Colchester) founded. And Roman expansion starts into Wales | ||

| 49- 50 | Foundation of Colonia Victricensis at Camulodunum. Mendip lead mines already in Roman hands. Legionary fortresses at Glevum and Lindum. Invasion of South Wales. | ||

50 | Caratacus, finally defeated in North Wales, flees to Cartamandua, queen of the Brigantes, and is surrendered to the Romans. | ||

52 | New Governor, D. Gallus. | ||

c.55 | Didius Gallus, governor, intervenes on the side of Cartimandua in Brigantian civil war. | ||

57 | New Governor, Q. Veranius | ||

58 | New Governor, S. Paulinus, attack on N. Wales. | ||

59-60 | Suetonius clears Britain totally of the Druids, with a final stand on Anglsea. | ||

60 | Suetonius Paulinus, governor, attacks Anglesey. | ||

60 | Pratagustus of the Iceni dies, and the Romans take his lands away from Boudica. | ||

60-61 | Boudica is elected war leader and leads a revolt agianst the Romans. (Read the story) Icenian revolt under Boudica suppressed after sack of Camulodunum, Londinium and Verulamium | ||

63 | New Governor, T. Maximus. | ||

65 | Preparations for campaigns in Wales. | ||

66 | One legion (XIV Gemina) withdrawn from Britain. | ||

| 68 | Army in Britain refuses to join the governor, Trebellius Maximus, in revolt against Galba. | ||

| 69 | Romans fail to prevent the defection of the Brigantes. | ||

| 69 | Civil Wars, New Governor, V. Bolanus. | ||

| 71 | New Governor, P. Cerialis. Conquest of Brigantia, capture of Stanwick? | ||

| 71-74 | Petilius Cerealis, governor, with a new legion (II Adiutrix) conquers the Brigantes. Legionary fortress at Eburacum. | ||

| 74-78 | Sextus Julius Frontinus, governor, subdues Wales and plants garrisons there. Legionary fortresses at Isca and Deva. | ||

| 78 | Julius Agricola, governor, completes the conquest of North Wales and Anglesey. | ||

| 79 | Consolidation of Brigantian conquest. | ||

| 80 | Advance to the Central Lowlands. | ||

| 81 | Agricola advances to the Forth Clyde line. | ||

| 82 | Conquest of south-west Scotland. | ||

| 83-84 | Agricola advances north and defeats the Caledonians at the battle of Mons Graupius. Roman fleet circumnavigates Britain. Legionary fortress at Inchtuthil. | ||

| 84 | After the Battle of Mons Graupius, occupation of N.Scotland. | ||

| 84-85 | Agricola recalled by Domitian. | ||

| 86 | One legion (II Adiutrix) withdrawn from Britain. | ||

| c.90 | Legionary fortress at Inchtuthil evacuated. | ||

| 90-96 | Foundation of Lindum Colonia at Lincoln. | ||

| 96-98 | Foundation of Colonia Nervia Glevensis at Gloucester. | ||

| 99-100 | Legionary fortress at Isca and many auxiliary forts in Wales rebuilt in stone. Scottish forts evacuated. | ||

| c103 | Legionary fortress at Deva rebuilt in stone. | ||

| 107-108 | Legionary fortress at Eburacum rebuilt in stone. | ||

| 117 | Revolt in north Britain. | ||

| 122 | Hadrian visits Britain. Legio IX Hispana replaced by VI Victrix. Construction of Hadrian's Wall from Tyne to Solway begun by Aulus Platorius Nepos. | ||

| 139-142 | Q. Lollius Urbicus, governor under Antoninus Pius, advances into Scotland and builds the Antonine Wall across the Clyde-Forth isthmus. | ||

| 155-158 | Rebellion in north Britain suppressed by C. Julius Verus. Antonine Wall temporarily evacuated. | ||

| 161-165 | Forts rebuilt by Calpurnius Agricola. | ||

| 180-184 | Further revolt in north Britain subdued by Ulpius Marcellus. Antonine Wall broken. | ||

| 193 | On the assassination of Commodus, Pertinax (lately governor of Britain) is chosen emperor by the Praetorian Guard but quickly killed. Empire auctioned to Didius Julianus, who is defeated by Severus. | ||

| 196-197 | Clodius Albinus, governor, takes troops from Britain to fight for the throne and is defeated by Severus. Hadrian's Wall, the fortress at Eburacum and many forts over run and destroyed by the Maeatae. | ||

| 197 | Virius Lupus restores the situation and rebuilds many forts. | ||

| 200-208 | Rebuilding of Hadrian's Wall by Alfenus Senecio. | ||

| 208 | Severus, Geld and Caracalla arrive in Britain and prepare for northern campaigning. | ||

| 209 | Severus and Caracalla campaign in Scotland and receive the surrender of the Caledonians. | ||

| 210 | Revolt of the Maeatae and second Scottish campaign. | ||

| 211 | Severus dies at York. Withdrawal to Hadrian's Walland organization of southern Scotland as a protectorate. | ||

| 212 | Caracalla extends Roman citizenship to all free provincials. Britain divided into two provinces. | ||

| 259-214 | Britain a part of the Gallic Empire of Postumus and his successors. | ||

| 275-287 | Saxon pirates in the Channel. | ||

| 287 | Commander of the British fleet, usurps the title of Emperor in Britain and Carausius, northern Gaul and is temporarily recognised by Diocletian and Maximian. | ||

| 293 | Carausius' continental possessions. Caesar reconquers Constantius. | ||

| 294 | Carausius murdered by Allectus, who succeeds him. | ||

| 296 | Britain restored to the legitimate emperors by Constantius, who crosses the Channel and defeats and kills Allectus. Barbarian inroads in the north. Hadrian's Wall and legionary fortresses at Eburacum and Deva rebuilt. Diocletian's reorganisation divides Britain into four provinces,separates the military from the civil administration and institutes new military offices. | ||

| 306 | Constantius, now emperor, with his son Constantine campaigns in Caledonia. Death of Constantius at Eburacum. | ||

| 313 | Edict of Milan grants toleration to the Christian Church. | ||

| 314 | Three British bishops attend the Council of Aries. | ||

| 343 | Constantine visits Britain and pacifies the Caledonian tribes. | ||

| 360 | Julian sends Lupicinus to repel raids of Picts and Scots. | ||

| 364 | Picts, Scots, Attacotti and Saxons raiding Britain. | ||

| 367 | Great invasion of Picts, Scots and Attacotti, aided by Saxon pirates and a simultaneous attack on Gaul by Franks.Treachery in the Wall garrison. Nectaridus, Count of the Saxon Shore, killed and Fullofaudes, Duke of Britain, routed. | ||

| 369 | Count Theodosius, sent by Valentinian I, clears Britain of invaders and restores the Wall. Signal stations built on Yorkshire coast. | ||

| 383 | Magnus Maximus, a military commander in Britain, revolts and conquers Gaul and Spain from Gratian. Hadrian's Wall swamped by invaders and not rebuilt. | ||

| 388 | Maximus defeated at Aquileia by Theodosius. | ||

| 395 | Stilicho improves the defences of Britain. | ||

| 406 | Constantine III, a usurper, strips Britain of troops for his conquest of Gaul and Spain. | ||

| 410 | Honorius tells the civitates of Britain to arrange for their own safety. Quote"...look to your own defences..." | ||

| c.446 | Last appeal of the British civitates to Aetius. | ||

| From this point on - whether you like it or not - Celtic Britain ends, or to be more precise Romano-British rule is no more. The Celtic peoples had spent 400 years mixing and marrying with the Romans and all the other peoples that came in smaller numbers from the Empire. For the last 100 years the Saxons had settled the south of England with the Roman forces unable to stop them. In fact the Romans paid the Saxons to keep the peace. When the Empire collapsed and the troops that remained were recalled, they had to run the gauntlet of the Saxon warriors all the way down to the ships on the coast. Many of them were robbed of their possessions on the way through, and some did not make it at all! What was left of the Romano-British in the south of Britain rallied around a military leader for a few years and kept the Saxons at bay. This shadowy figure is what all the Arthurian stories are based on. | |||